In early 2019 my team at Southwest Research Institute swore a solemn oath: any new robotic systems we develop will use ROS2. ROS Noetic will be the last ROS release, as the community shifts its focus to building and supporting new ROS2 releases. We agreed that it was crucial to commit early and get substantial hands-on experience with ROS2 well in advance of this upcoming transition.

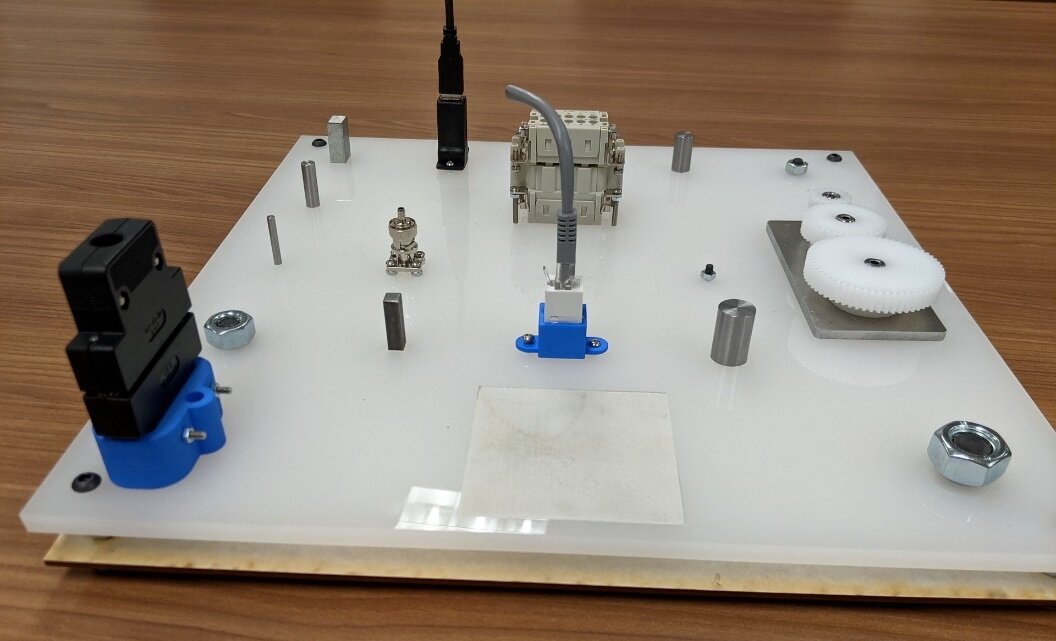

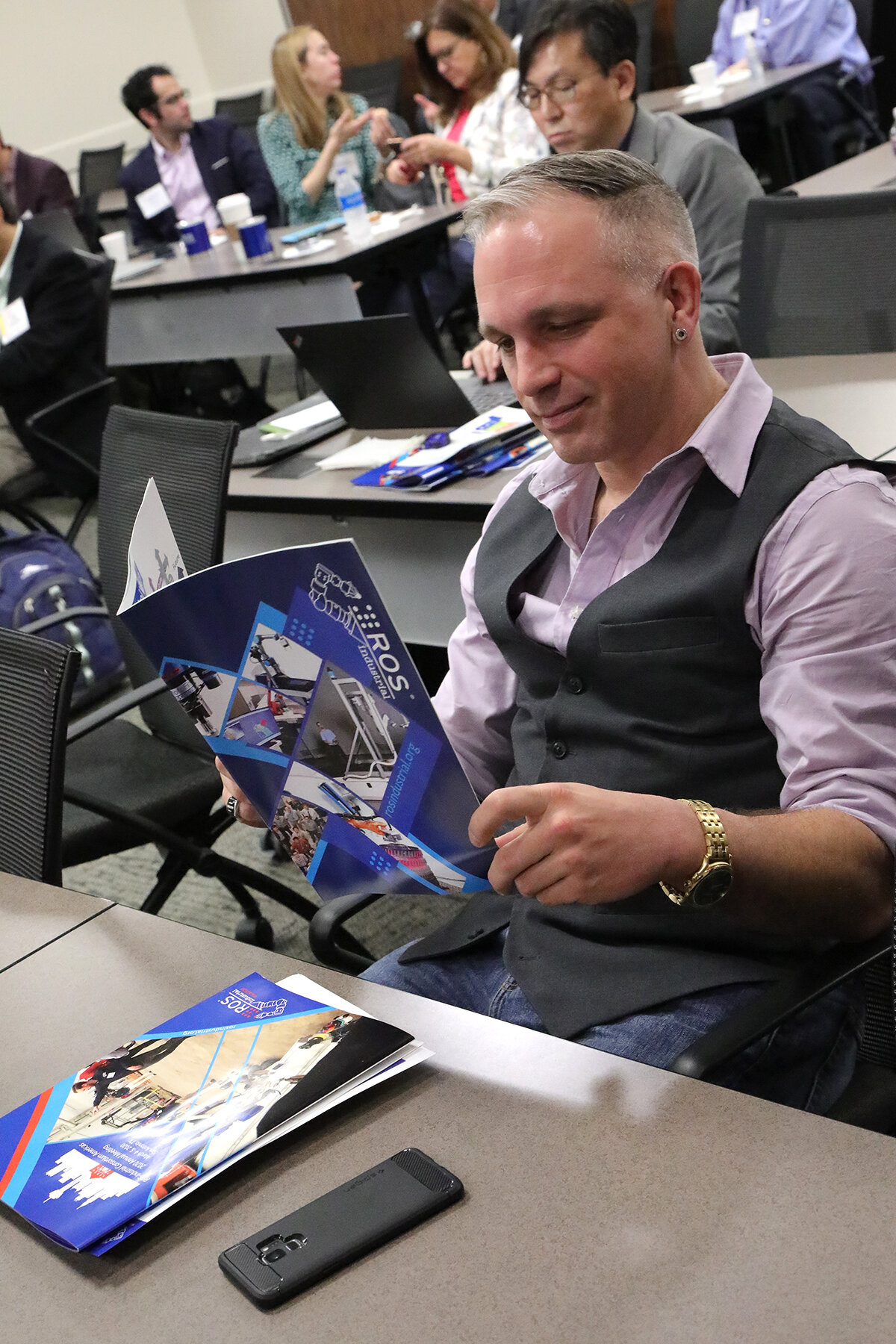

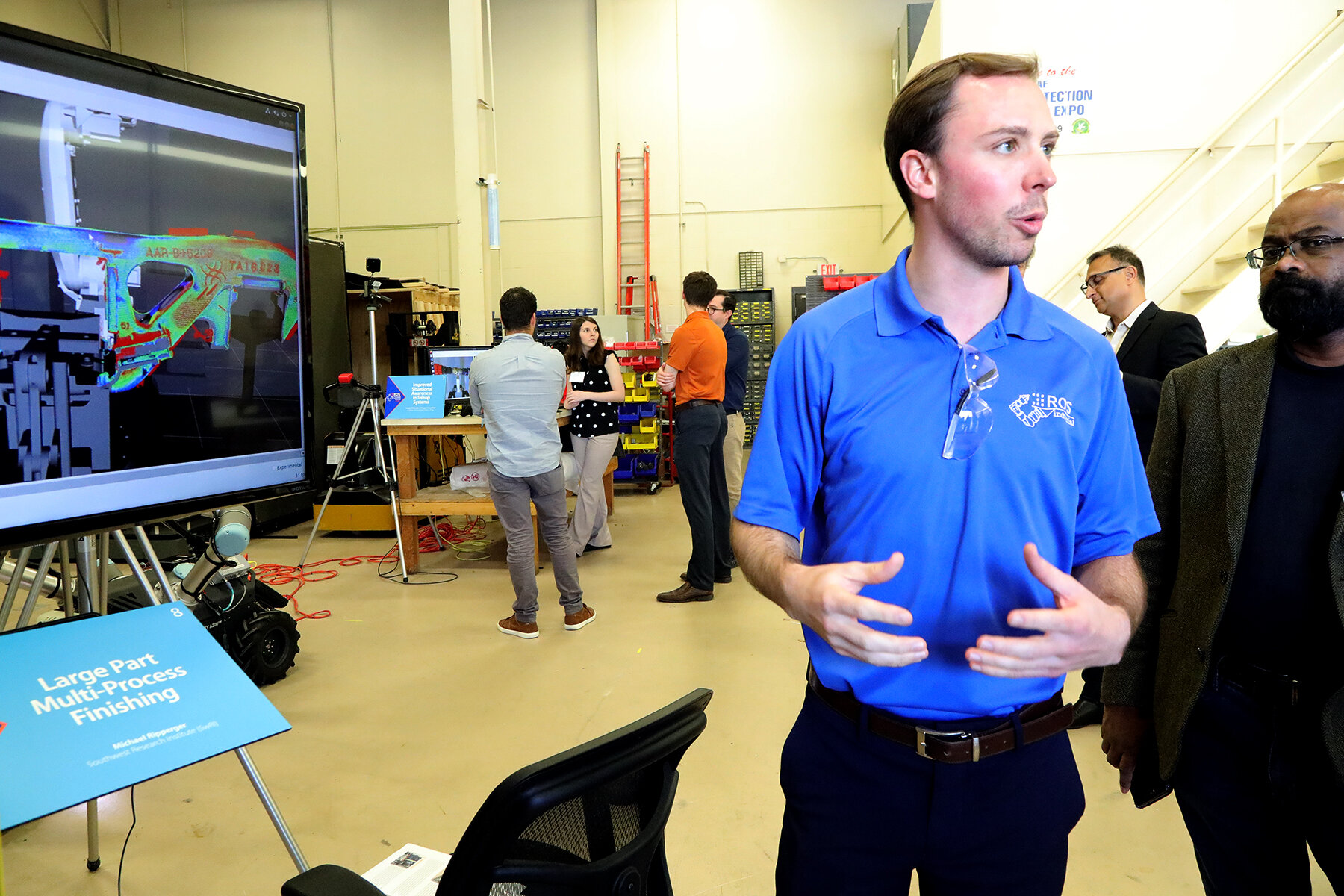

Our first opportunity to apply this philosophy to a system intended for a production environment came in Spring 2019. We began a new project to develop a greenfield collaborative Scan-N-Plan system for an industrial client, which I will refer to here as Project Alpha. Several months ago, we completed and shipped Project Alpha, making it one of the first ROS2 systems to be deployed commercially.

The purpose of this article is to describe some of the discoveries made and lessons learned throughout this project, as we begin to apply this knowledge to the next generation of ROS2 systems.

Why is developing in ROS2 important?

There is a “chicken and egg” problem surrounding developing in ROS2. The most important part of ROS has been the lively and diverse package ecosystem, since the ability to bring in ready-to-ship packages supporting a wide variety of sensors and robots presents a huge advantage for roboticists. While the core rclcpp packages are fully-featured and robust, we need more ROS2 interface packages for sensors and robots commonly used in robotic applications. This gap presents a dilemma: potential users are discouraged from committing to ROS2 due to a lack of support for their hardware, which reduces the incentive for vendors to develop and support new ROS2 packages for their products.

In order to break this cycle, a critical mass of developers needs to commit to ROS2 and help populate the ecosystem. There are certainly benefits for early adopters: Intel’s family of RealSense RGB-D cameras had very early ROS2 support, and as a result, this camera has become a go-to 3D perception solution for ROS2 projects.

Integrating a Robot

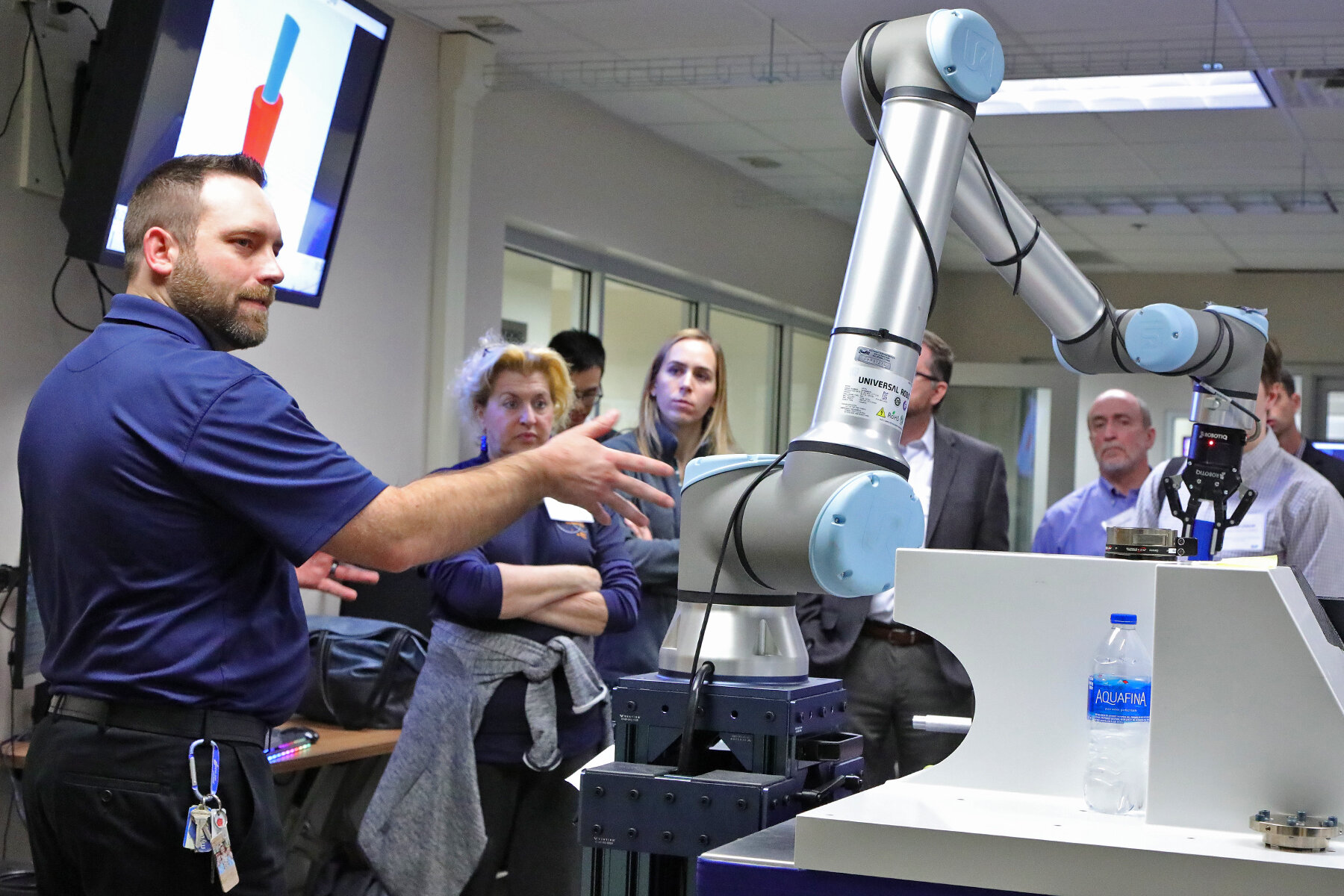

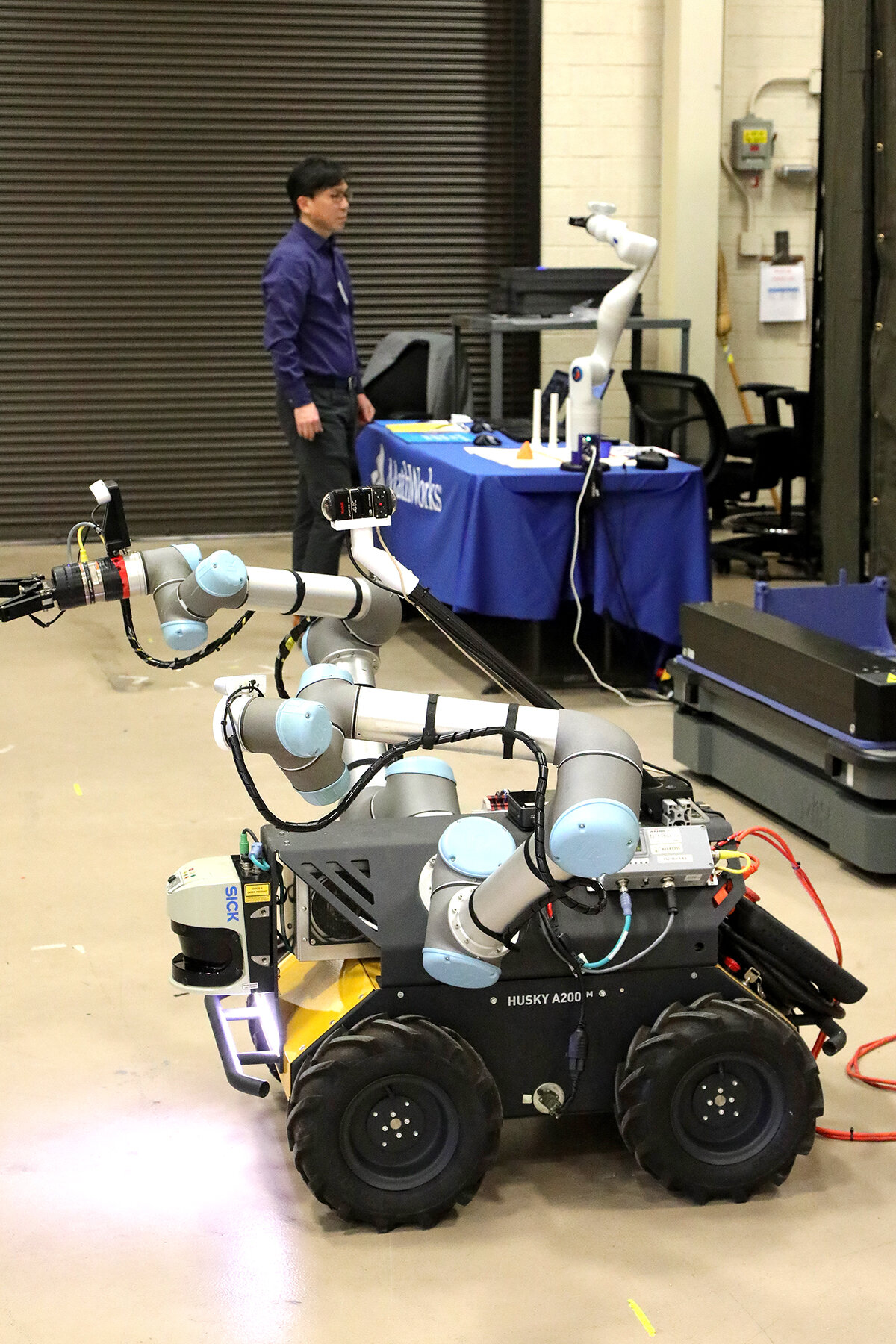

We decided to build Project Alpha around the Universal Robots UR10e. Its reach, payload capacity, and collaborative capability satisfied our application-specific requirements. Additionally, we had experience integrating URs with prior projects, and we already had a few on hand in our lab. Fortuitously, the start of the project coincided with the beta release of the excellent Universal_Robots_ROS_Driver package, which has become our driver of choice.

However, there was a substantial immediate challenge: the UR robot driver was a ROS1 package, and we were developing a ROS2 system. There is very little ROS2 driver support for industrial robots, since the process of developing new robot drivers needs significant specialized effort. To address this challenge, we encourage the community to overcome this obstacle and invest the effort to develop new ROS2 drivers for industrial robots.

For the time being, the ros1_bridge package was sufficient to relay joint_state topics and robot control services between the ROS1 and ROS2 networks. We also adapted a custom action bridge node to convey FollowJointTrajectory action goals from our ROS2 motion planning and execution nodes to the ROS1 UR driver node. With these pieces in place, we were ready to plan!

Writing New Nodes

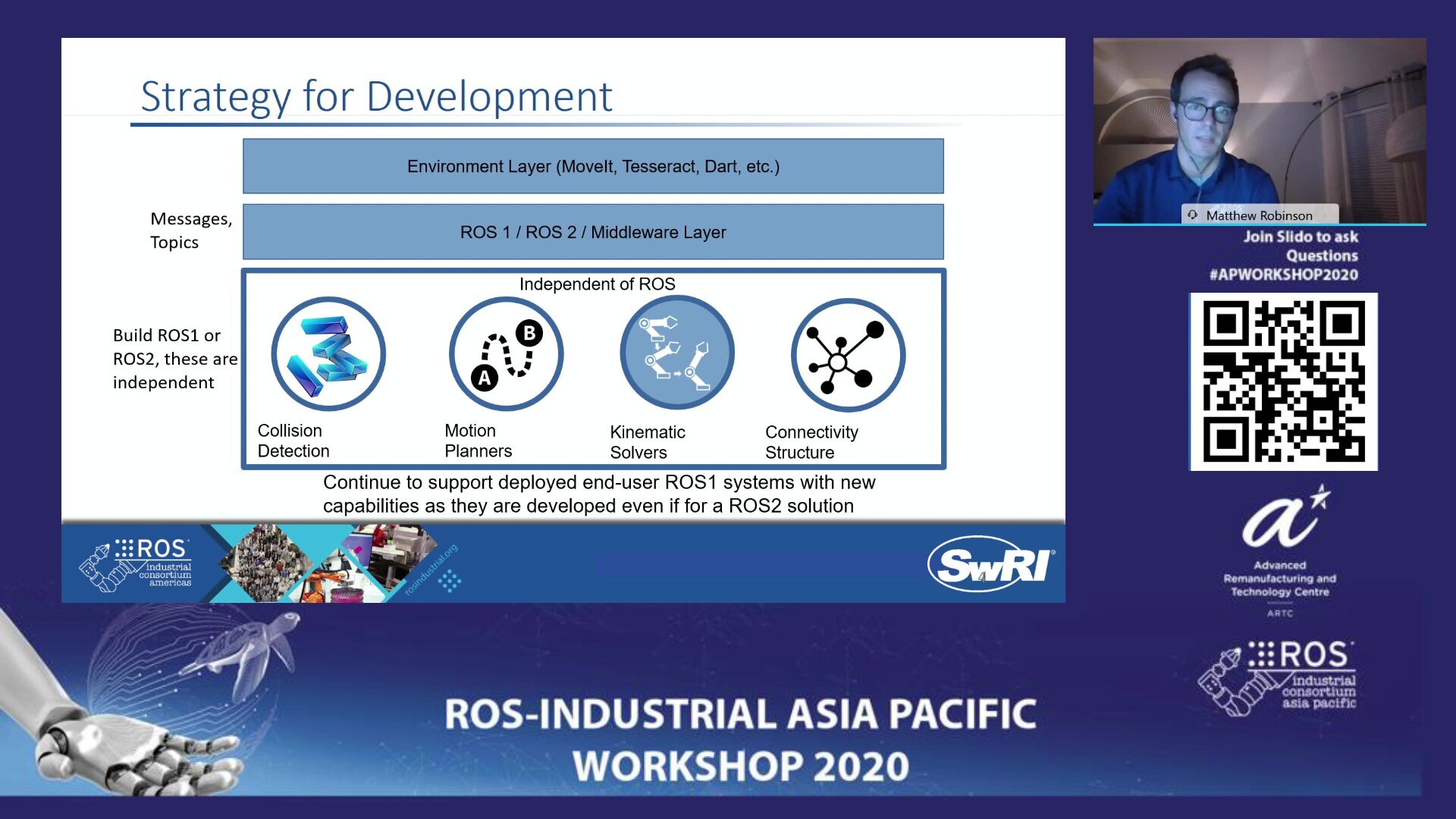

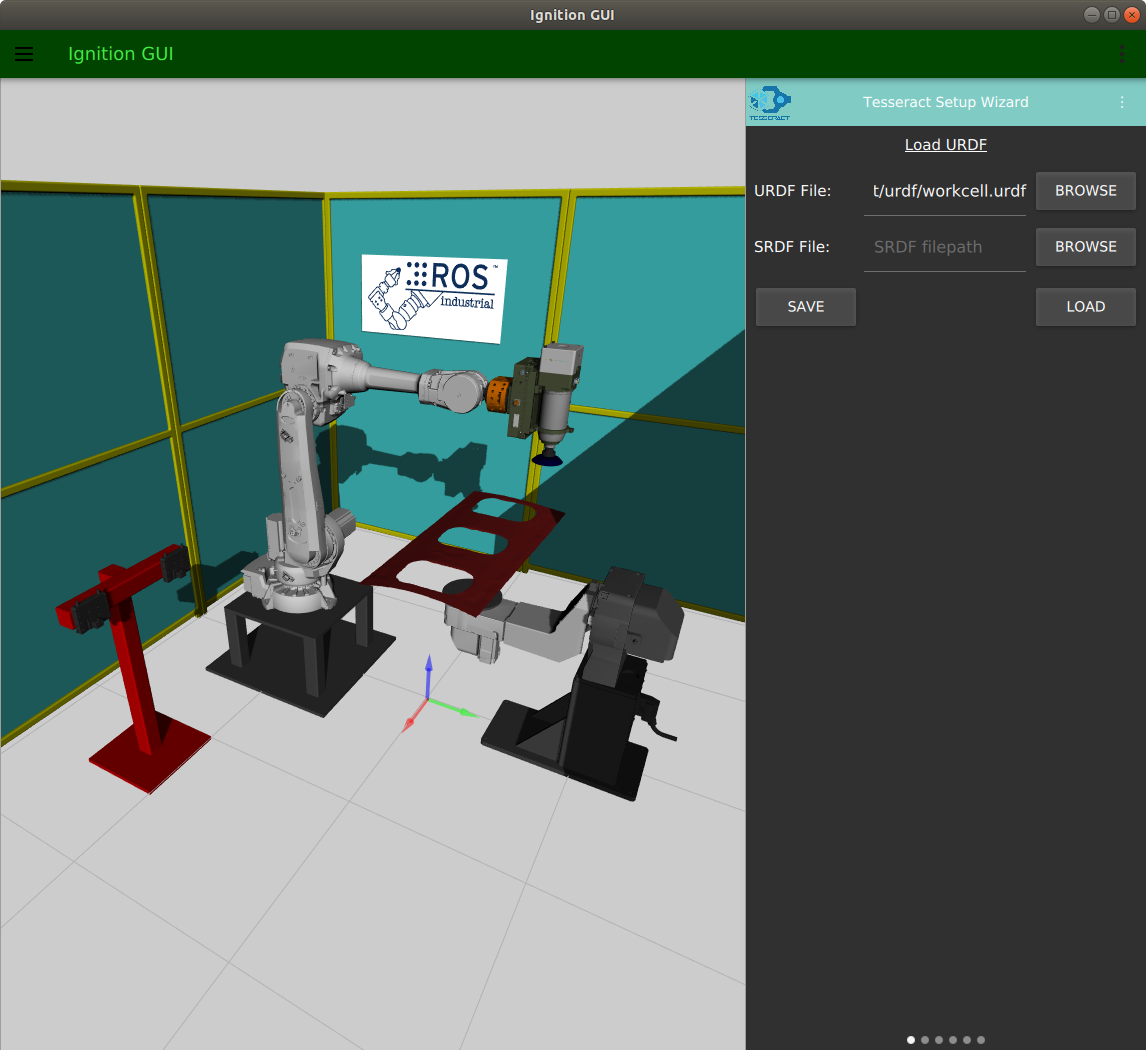

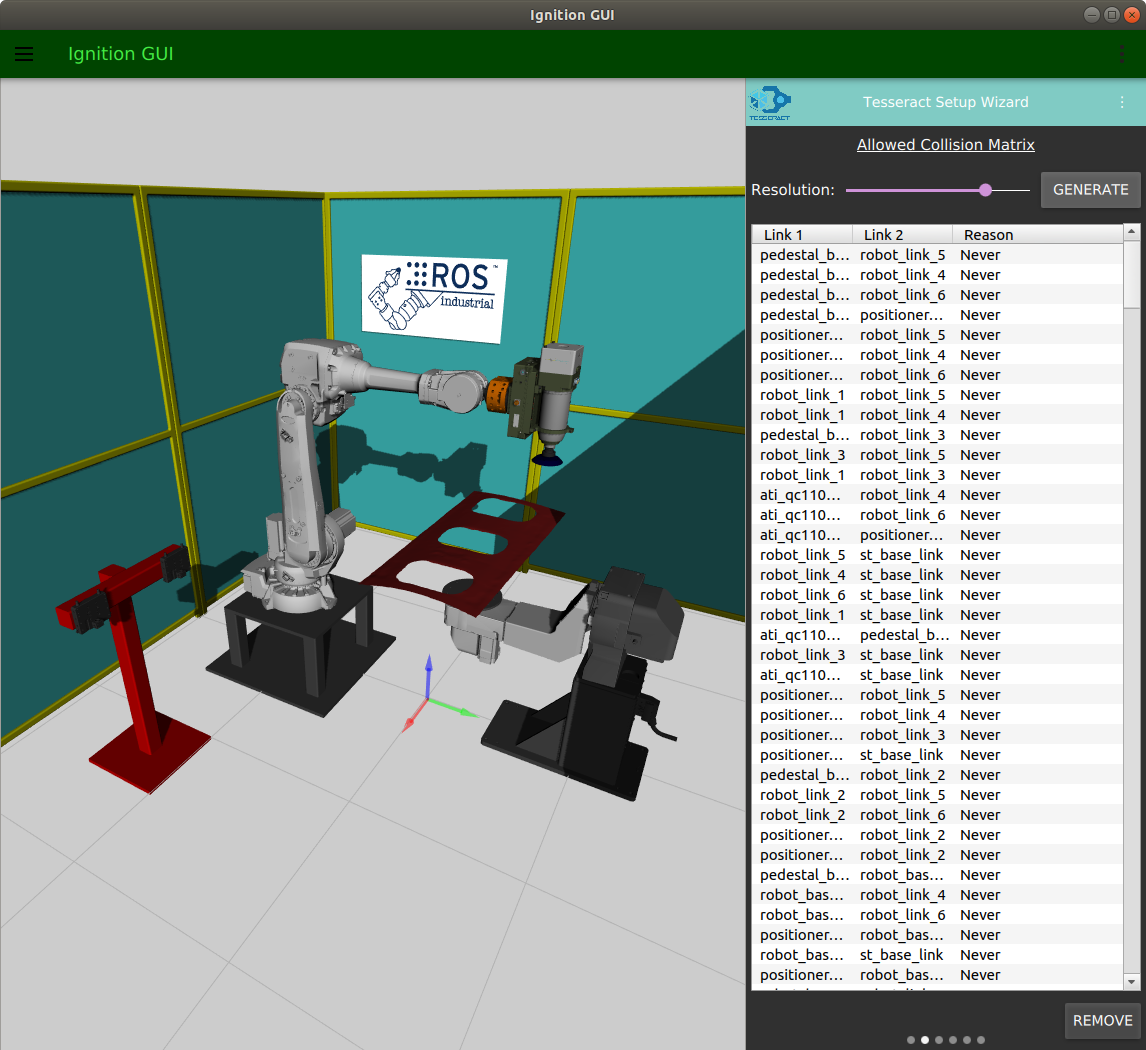

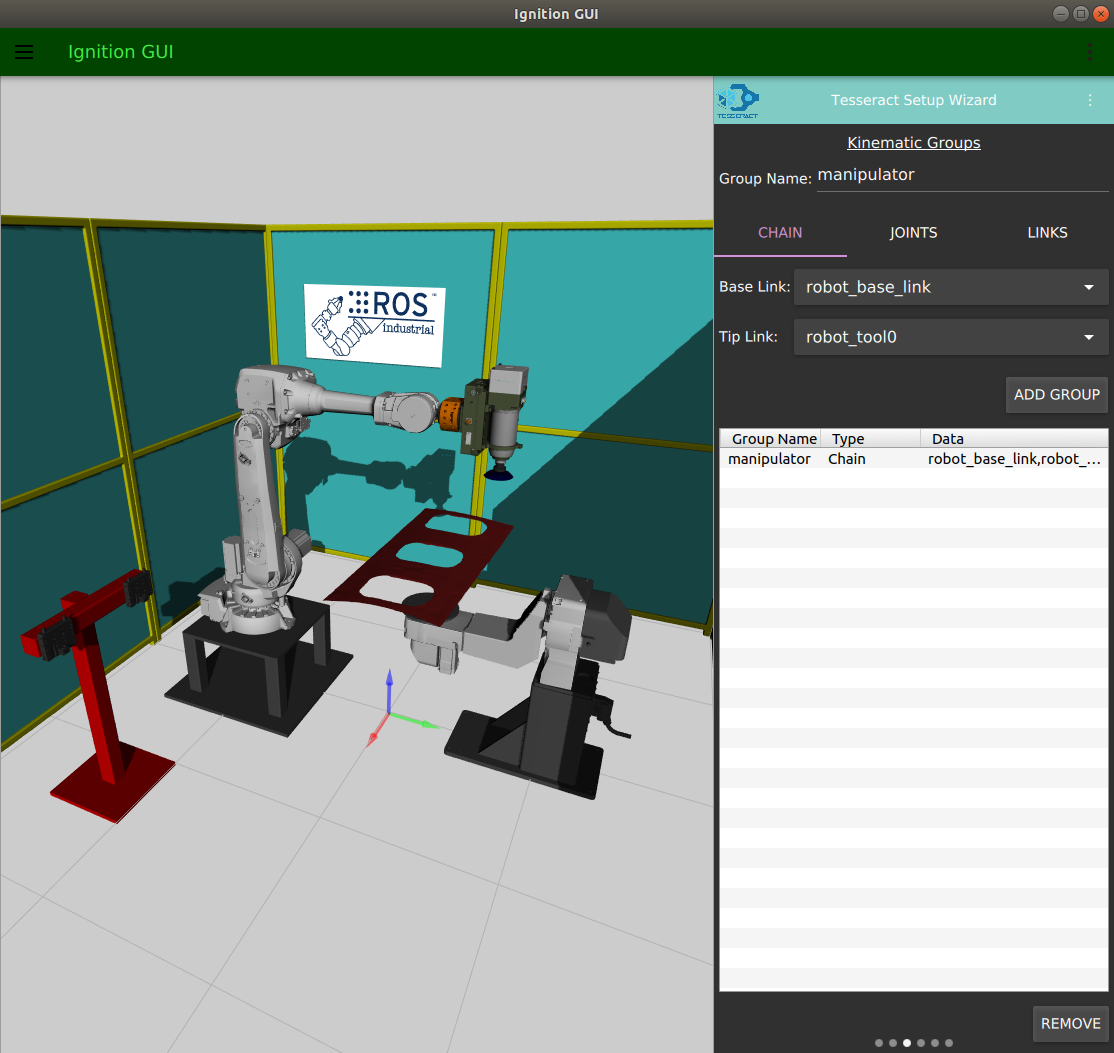

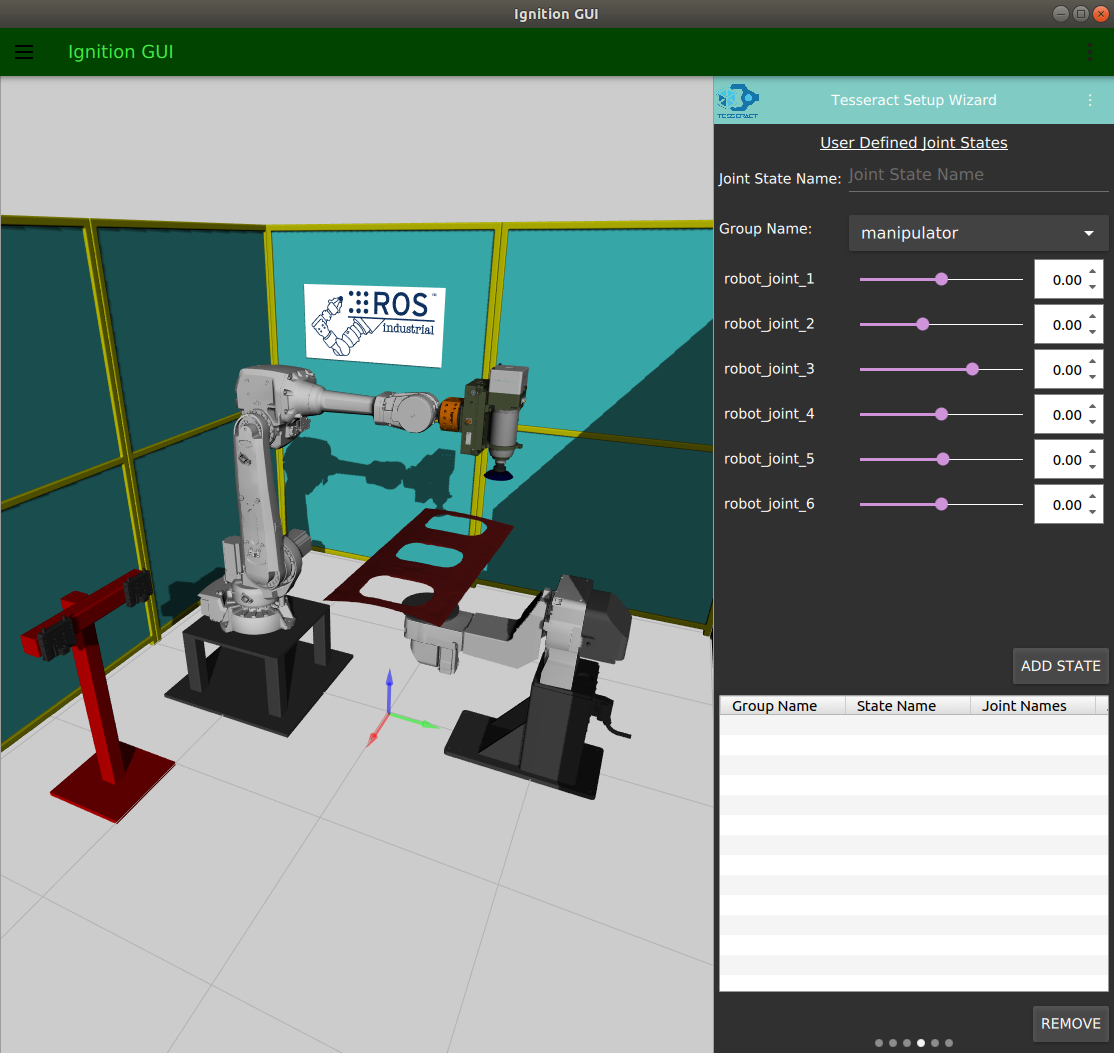

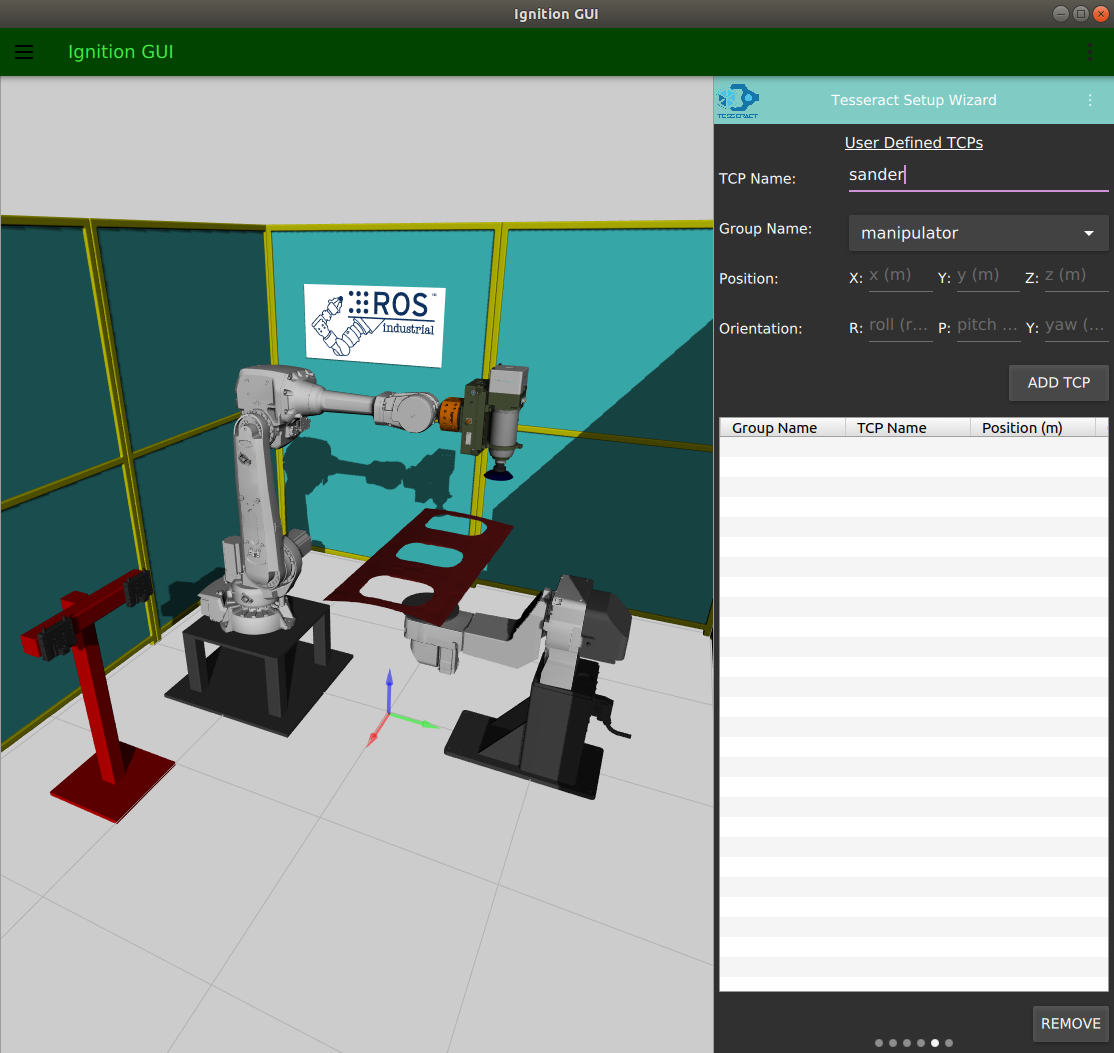

While our robot was ready to move, there was no ROS2-native motion planning pipeline available. At the time, MoveIt2 was still in an alpha state and and was undergoing significant development. To address this gap, we decided to port our Tesseract motion planning library to ROS2. This effort resulted in three repositories: the ROS-independent Tesseract core repository, the ROS1 tesseract_ros repository, and its close ROS2 sibling, tesseract_ros2.

As we worked through the ROS2 port of Tesseract and created new system-specific ROS2 packages for Project Alpha, we found ourselves discovering a new set of best-practice approaches for ROS2. For example, there are two distinct approaches when creating a C++ ROS2 node:

Pass in a Node instance: Create a custom class that takes a generic Node object in its constructor. This is similar to how NodeHandle objects are used in ROS1. These classes are flexible: they can be wrapped in a thin executable as standalone nodes or included as one aspect of a more complex node. The core mechanisms of the class can be exposed both through C++ functions and through ROS2 services.

Extend the Node class: Create a class that inherits from and extends the base ROS2 Node class and add application-specific member variables and functions. I get the impression that this is more in-line with the design intent of ROS2, since key functionality like logging and time measurement is exposed as member functions of the Node class. This approach also exposes new capabilities unique to ROS2, like node lifecycle management.

Ultimately, we used both approaches. We found that the first strategy made it easier to directly port ROS nodes, so the nodes in the tesseract_ros2 package use this method. For the newly-developed Project Alpha nodes we used the second strategy, since we had much more freedom to design these new nodes from scratch to make the most of ROS2.

Working with DDS Middleware

The ROS2 DDS communication middleware layer represents a substantial improvement over the TCP/IP-based system used in previous ROS versions. ROS2 ships with a variety of RMW (ROS MiddleWare) implementations provided by several DDS vendors. Fortunately it is very straightforward to switch between the different RMW implementations: all that is required is to install the packages for the new RMW version, set the RMW_IMPLEMENTATION environment variable to specify the desired version, and rebuild any built-from-source packages in your workspace that provide message definitions.

Surprisingly, the choice of which RMW implementation we used had a substantial effect on the performance of Project Alpha, although this did not become clear until relatively late in development.

At the beginning of the project we used FastRTPS, which was the default option for ROS2 Dashing. It worked well for our initial collection of nodes, but when we integrated the ROS driver for the UR10e robot we began experiencing dropped messages and higher latency. Our theory is that the high volume of messages produced by the UR10e's real-time control loop overwhelmed the RMW layer under its default settings. We began exploring alternatives.

Our next option was OpenSplice, which eliminated the issue of dropped messages with the UR10e. However, we discovered several new issues: nodes took several seconds to fully initialize and begin publishing messages, and topics advertised by newly-launched nodes would often not be visible to nodes that were already running. Project Alpha's nodes were designed to all launch together at system startup and stay alive the whole time the system was running, so we were able to work around this issue for some time.

When we updated Project Alpha to use ROS2 Eloquent, we decided to try out the newly-available CycloneDDS RMW implementation. We discovered that it was not susceptible to any of our previous issues: it allowed our nodes to launch quickly on startup, handled high-rate topics as well as large messages like high-resolution point clouds, and could also gracefully manage nodes arbitrarily joining and leaving the network. Project Alpha was shipped to the client configured to use CycloneDDS.

Conclusions

Project Alpha has been a success, and we have been able to leverage our ROS2 development experience to pursue new projects with confidence. We were able to answer some important questions:

Is it better to develop pure-ROS2 systems or hybrid ROS/ROS2 systems? It is preferable to develop and maintain an exclusively ROS2 system. Hybrid systems will be a reality for some time until the development of the ROS2 ecosystem can catch up.

What ROS2 release should be used? We consistently found that there were substantial benefits to using the latest ROS2 release, in the form of new features and functionality.

Is ROS2 "ready for industry?" Resoundingly, yes! Get out there and build ROS2 systems!